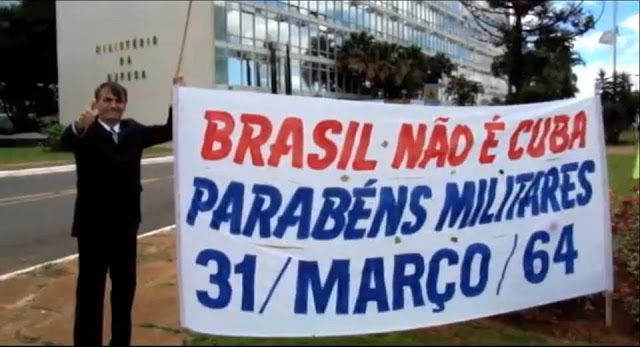

As Brazilians rightly celebrate the 56th anniversary of the military intervention that saved their country from a communist takeover, which would result in the inevitable loss of countless innocent lives, I think it is most appropriate to explain the context by which the army officers were called by the people to depose a highly unpopular, leftist political ruler. What follows is an account of the most important events surrounding that momentous event in the constitutional history of Brazil.

During World War II the country’s participation in that war brought about demands for its democratisation. It was indeed a great contradiction to be governed by an authoritarian regime bearing some similarities to those the Brazilians helped defeat on the old continent. Many started questioning why Brazilian soldiers had gone to Europe to fight against fascism when it had a political regime at home that was not too dissimilar. An October 1943 manifesto, signed by ninety personalities of Minas Gerais, declared:

If we are fighting against fascism on the side of the United Nations, so that liberty and democracy may be restored to all people, certainly we are not asking too much in demanding for ourselves such rights and guarantees.

Under such pressure, Brazil’s dictator Getulio Vargas attached, in February 1945, an amendment to the Charter of 1937. In doing so, he signalled the intention to relinquish power by announcing democratic elections for president and members of National Congress. He also announced the advent of elections for state governors and state legislative assemblies, and later, in April 1945, he also freed political prisoners.

But Vargas ended up being ousted on 29 October 1945, in a military manoeuvre carried out without bloodshed or social reaction. The action took place four days after Vargas nominated his bad-tempered brother Benjamin Vargas as Chief-Police of the Federal District (Rio de Janeiro). The strategy did not work as Vargas had hoped, and he was subsequently forced to resign by his own minister of war, General Góes Monteiro. Even though he was ousted by the army officers, Vargas described himself as a victim of ‘foreign finance groups’ who had conspired with the opposition to restore ‘old liberal capitalist democracy’. But in reality, as the American historian Thomas Skidmore explains:

The dictator was sent from office not by the power of the civilian opposition, but by decision of the Army command. It was not, therefore, a victory earned by the political influence of the liberal constitutionalists.

With the end of President Vargas’ Estado Novo, special legislation from November 1945 conferred on both houses of National Congress the power to meet jointly in Assembléia Constituinte (Constituent Assembly). Elections for the constituent assembly were held in December 1945, and its elected members started the draft of the new constitution in February 1946. The final result was a Constitution that provided for democratic elections, protection of basic human rights, judicial independence, and restriction of federal intervention in state affairs. Moreover, the legislature recovered its legislative supremacy over the executive, and the right to vote was granted to all Brazilians of both sexes from the age of 18, with the exception of the illiterate or those enlisted in the armed forces.

Because the 1946 Constitution prohibited the functioning of undemocratic parties, a May 1947 decision of the Supreme Court (STF) outlawed the Communist Party of Brazil (Partido Comunista do Brasil – PCB). After all, their communist leader, Luiz Carlos Prestes, had publicly described the constitutional order as illegitimate, and a mere product of ‘bourgeois democracy’. He had once publically stated that that the Communist Party would enthusiastically support the Soviet Union in the eventual advent of war against Brazil.

The suicide of President Vargas in 1954 was a hard test for the newly established democratic system. Elected by the people in 1950 as their new president, the former dictator encountered many difficulties to rule as a democratic leader. He obviously lacked the necessary ability to govern under the rule of law. He soon entered into direct conflict with the members of National Congress, who weren’t always keen to obey everything he wished. On at least one occasion, Vargas lost his patience and warned the Congress about the day in which the masses would ‘take the law into their own hands’.

Vargas’ administration at that time was accused of widespread corruption, public graft, embezzlement and illicit gains. His end became imminent following the failed attempt of his cronies, on 5 August 1954, to kill the Governor of Rio de Janeiro, the outspoken journalist Carlos Lacerda. Lacerda was only slightly wounded but Air Force Major Rubens Vaz, who was walking with him, was killed. It was soon found that the President’s bodyguard, Climério de Almeida, was directly responsible for the crime. He confessed under interrogation that Lutero Vargas, President Vargas’s son, had ordered the assassination attempt of Governor Lacerda. It was further revealed that Almeida had been paid to do the “job” by the chief of the presidential guard, Gregório Fortunato.

Under such circumstances President Vargas had no option but to offer a letter of resignation. And yet, he did so in a most unexpected way, by committing suicide on August 24, 1954. In so doing, Vargas left behind a letter describing himself as ‘a victim of a subterranean campaign of international groups joined with national interests, revolting against the regime of workers’ guarantees’. The suicide led to a wave of violent actions against his political adversaries and on foreign properties. It conveniently transformed Vargas into a sort of patriotic martyr for far too many people.

In having no direct links with Vargas, the 1960 election of Jânio Quadros was seen as a possible rupture within his legacy. Quadros, however, was a populist who sometimes appeared to regard the rule of law as an undesirable obstacle to his own exercise of power. Indeed, the doctrine of separation of powers between legislative and executive was not entirely appreciated by him, which caused an inevitable clash between the impulsive President and the federal legislative.

On 25 August 1961, President Quadros stunned the entire nation by offering his letter of resignation. Apparently he wished to provoke an institutional crisis which he hoped could cause a popular reaction and demand for his return to office; this time ruling as a populist dictator. Quadros rationalised that Brazilians wanted a ‘stronger’ government, and that governing together with the legislative was not necessarily conducive of such an objective. His artifice, however, proved an absolute failure and he never returned to power.

When President Quadros offered his resignation, his vice-president João Goulart was serving in a diplomatic mission in communist China. Goulart had been Vargas’ labour minister, in 1953. He was a close friend of Argentina’s fascist leader Juan Domingo Perón, whose authoritarian regime relied particularly on trade-union support. Elected as vice-president with no more than 34 percent of the valid votes, Goulart did not have the support of the majority of Brazilians. Besides, he was an anathema to the business sector and to the majority of army leaders. Congressmen then decided, on 3 September 1961, to establish a parliamentary system by amending the 1946 Constitution.

While President Goulart was fighting to restore presidential power, his first year of government was relatively peaceful and stable. After the popular plebiscite of 1963 went on to re-establish the presidential system, Goulart felt more comfortable to develop closer diplomatic ties with communist regimes, in particular China, Cuba and the Soviet Union. Indeed, so confident he suddenly became that Goulart even told U.S. ambassador Lincoln Gordon, in 1962, that the parliament had lost popular support and so he could ‘arouse people overnight to shut it down’.

What is more, President Goulart notoriously supported the Pro-Castro agrarian movement called Ligas Camponesas, in the north-eastern region of Brazil. This organisation not only handed out millions of Mao Tse-Tung’s essays on guerrilla tactics, but it was found also that two of its farms bought with money sent by Fidel Castro were being used as training centres for guerrilla warfare. The radicalisation process was so significant that, in 1963, an American communist visiting Brazil reported that ‘potential Fidel Castros’ were already seizing the lands. ‘With conditions getting worse’, he argued, ‘the final result will be a dictatorship of the Left, as in Cuba’.

Indeed, sociologist Gilberto Freyre argued in 1963 that Brazil was effectively experiencing a ‘state of revolutionary ferment, on the verge of becoming the new China of the West’. Alfred Stepan, who was government professor at Columbia University and later the director of its Center for the Study of Democracy, agreed with him. As noted by Stepan, the 1959 Cuban Revolution had the undesirable effect of reinforcing the undemocratic nature of the Left and its ideological commitment to the use of violence as a valid political weapon. ‘In the already turbulent Brazilian situation’, Stepan stated:

The effect of the Cuban revolution on the civilian left was to increase their belief in the efficacy of the tactics of violence. At the least, it helped sweep up the radical nationalists in the rhetoric of a Cuban-style revolution. Catholic student activists (Ação Popular) entered into electoral coalitions with Communist students after 1959, and looked to Cuba as a revolutionary model. Peasants leagues invaded the land in the northeast, and President Goulart’s brother-in-law, Leonel Brizola, urged the formation of revolutionary cell of eleven armed men (the grupos de onze).

The communist leaders of the Soviet Union were deeply interested in that particular development. In February 1964, Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev convened the leader of the Brazilian Communist Party, Luis Carlos Prestes, for an official briefing at the Kremlin. Prestes told him about the ‘great prestige’ enjoyed by the communists in the Goulart administration. When invited to speak at the Soviet Supreme, he stated that anyone who dared to resist the advance of communism in Brazil would have their heads cut off. So confident he was of the country’s communist future that the community party’s printshop in São Paulo was already printing large supplies of postage stamps, pamphlets, and bank notes displaying the portraits of Lenin, Stalin and Prestes himself.

On 3 October 1963, President Goulart requested the approval of the federal legislative for martial law, allegedly to fight against subversion. Had it been granted, such measures would allow the President to confiscate farms and private companies. The decision was delayed and, knowing it eventually would be rejected, Goulart, himself, withdrew the request a few days later.

By the end of that year, however, the parliament remained in extraordinary session over the Christmas break, fearing that Goulart could decree martial law while its was in recess. Meanwhile, his brother-in-law, Leonel Brizola, demanded the dissolution of Congress, to be replaced by a ‘popular assembly’ consisting of ‘workers and peasants’. In September 1963, Brizola declared to law students at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro:

If the democracy we enjoy continues to be used as a screen for laws concealing the plunder of our people, we solemnly declare: We reject such a [democratic] system as an instrument of oppression and domination of our native land, and we shall use the methods of struggle at our disposal.

In his January 1964 Presidential Address delivered at the National Congress, Goulart warned that a ‘bloody convulsion’ would take place if the parliamentarians dared not approve the unconstitutional reforms desired by him. On 13 March 1964, Goulart went even further and promised supporters attending a rally at the Central Railroad Station of Rio de Janeiro that he would carry out confiscation of land and private companies with or without parliamentary approval.

Surely he could not carry out any such measures, because they required amendment to the Constitution and the majority in both houses of Congress were fiercely against them. Still, Goulart promised to modify ‘institutional methods’ to make them happen. Speaking on behalf of his brother-in-law, Leonel Brizola declared that the presidency no longer recognised Congress as the nation’s legislative body. According to Phyllis R. Parker, the author of ‘Brazil and the Quiet Intervention’,

His inflammatory discourse dramatically called for throwing out the Congress and for holding a plebiscite to install a Constitutional Assembly with a view to creating a popular congress made up of labourers, peasants, sergeants, and nationalist officers, and (sic) authentic men of the people.

The rally of March 13th broached such prospects as repealing the Brazilian Constitution and closing down the National Congress. After that the army officers started to strongly suspect that President Goulart would attempt to introduce unconstitutional reforms, by pressuring or even closing down the federal parliament. In other words, they became more fully convinced that Goulart was planning to stay in power and to rule as a populist dictator. There was no doubt that he was effectively seeking to establish a left-wing dictatorship.

However, surveys carried out in early 1964 indicated that just 15% of the population supported the leftist President. On March 19, 1964, São Paulo city held the Marcha da Família com Deus pela Liberdade (March of the Family with God for Freedom), a massive rally of one million people who opposed President Goulart. Organisers described the event as an effort to protect Brazilians from the fate and suffering of the martyred people of Cuba, Poland, Hungary and other enslaved nations. A few days later, a second rally brought 150,000 people took the streets of Santos, another important city in São Paulo state.

In September 1963, President Goulart refused to condemn a mutiny of sergeants, believing his government could neutralize army generals who were more actively opposed to him. He also refused, on 26 March 1964, to punish another mutiny carried out by marines who refused to cease political activities and return to their duties. In fact, the President even went so far as to dismiss the Navy Minister, who attempted to quell the revolt. An editorial of the daily Jornal do Brasil reported:

The rule of law has submerged in Brazil… Only those who retain power of acting to re-establish the rule of law remain effectively legitimate… The armed forces were all – we repeat, all – wounded in what is most essential to them: the fundamentals of authority, hierarchy, and discipline… This is not the hour for indifference, especially on the part of the army, which has the power to prevent worse ills… The hour of resistance by all has now arrived.

The naval mutiny brought about a common view among the army officers that now Goulart had gone too far. Many of those army leaders were initially opposed to any extraordinary step, but now it was the President’s sanctioning of military indiscipline that forced them to change their minds. They began to suddenly realise that if the supreme executive authority refuses to obey the law, he then automatically loses the right to be obeyed because his own authority emanates from the Constitution.

Furthermore, the armed forces were compelled by Article 177 of the 1946 Brazilian Constitution to defend the country and to guarantee the constitutional powers, law, and order. Eventually, on 20 March 1964, the governor of Minas Gerais, Magalhães Pinto, appeared on television to state that he would resist any attempt by the President to arbitrarily dissolve the Congress. Similarly, the governor of São Paulo, Adhemar de Barros, also went on television to declare that his state would follow Minas Gerais and resist any ‘self-coup’ from Goulart.

The army intervention that finally deposed President Goulart began with a radio proclamation, on 31 March 1964. General Olimpio Mourão, the commander of the 4th Military Region based in Minas Gerais, accused the President of providing communists with ‘the power to hire and fire ministers, generals, and high officials, seeking this way to undermine true democratic institutions’. The ‘masses’, in whose name Goulart so often spoke, were nowhere to be found. Instead, when Goulart was sent into exile to Uruguay, on 1 April 1964, millions packed the streets of the major cities to celebrate his overthrow. And even the Brazilian Bar Association manifested itself in favour of such intervention, acknowledging the failure of Goulart to respect democracy and the rule of law.

Although the left in Brazil consoled itself by blaming external forces for President Goulart’s overthrow, in particular the United States, this actually required no outside aid. In fact, there was a massive popular support for his overthrown by the army leadership. Such support was substantially bigger than any scattered effort to save an utterly demoralised President. For those who lived in the country at that time, it really seemed as if the only three possible alternatives were military intervention, communist rule, or total anarchy. Brazilians then wisely opted for the first option. This is how the 20-year period of military government in Brazil started, but that’s another story.

Dr Augusto Zimmermann PhD (Mon.), LLM cum laude (PUC-Rio), LLB (PUC-Rio), DipEd, CertIntArb is Head and Professor of Law at Sheridan College in Perth, Western Australia, and Professor of Law (Adjunct) at the University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney campus. He is also President of the Western Australian Legal Theory Association (WALTA), Editor-in-Chief of the Western Australian Jurist law journal, and a former Commissioner with the Law Reform Commission of Western Australia (2012-2017). Dr Zimmermann is also the recipient of the Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Research, Murdoch University (2012). He is the author of numerous Brazilian law books and articles, including ‘Direito Constitucional Brasileiro’ (Lumen Juris, 2014) a 1,000 page, two-volume book on Brazilian constitutional law co-authored by Fabio Condeixa.